Some Venetian patere show this unusual iconography: a female figure holding a big fish in her arms. She is a sort of syren, the lower part of her body ending in a long neck and a animal head instead that in a fish tail.

This part of the body has often been described as a swan, but let's observe that it is not a bird: it is fin-footed, and the fin is not of that of a fish, rather of a seal.

Elephant seal (Cystophora proboscidea) / vintage illustration from Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 1897

Credits: Hein Nouwens via Shutterstock.com

The motive of a pretty, long-haired female figure with a (disproportioned) fish under her arm recalls the celestial Andromeda.

As we know from the Greek myth, Andromeda, the utmost beautiful but unfortunate princess of Ethiopia, had been condemned to be devoured by a sea monster sent by the sea God Poseidon, and in consequence chained to a rock by the sea; so she appears among the figures in the classical sky: open-armed and in chains, ready for her sad fate.

However, her closed proximity to another well-known constellation, the two Zodiacal Fishes, (particularly to the Northern one, or Piscis Boreus), has transformed her from the Chained Princess into the "Woman with fish(es)". Like here:

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿUmar al-Ṣūfī, Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-ṯābita ("Book of the Fixed Stars"), 1430-1440, a revision of Ptolemy's Almagest with Arabic star names and drawings of the constellations, 1430-1440.

Anoymous and non-dated copy produced in Samarkand (present Uzbekistan)

Paris, BNF, MS Arabe 5036, fol. 247v

Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF

Sometimes, one or both Fishes penetrate Andromeda's side; this happens particularly in the Arab and Persian representations.

From ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿUmar al-Ṣūfī, Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-ṯābita ("Book of the Fixed Stars"), 1430-1440.

Paris, BNF, MS Arabe 2489, fol.69v

Why that?

Because some of these representations come from latitudes in which the sky is observed from a different perpective.

As we know, when an observer moves towards the South on the surface of the Earth, some of the images in the sky that we call constellations appear to change their orientation and (slightly) their shape. This is the case, for exemple, with the celestial horse Pegasus (see previous posts): if observed from North of a certain latitude, Pegasus appears capsized, legs in the air; but, as the observer moves southwards, it slowly turns on himself, until it becomes a normally standing horse.

Also Andromeda, Pegasus' neighbor in the heavens, changes perspective as we move southwards.

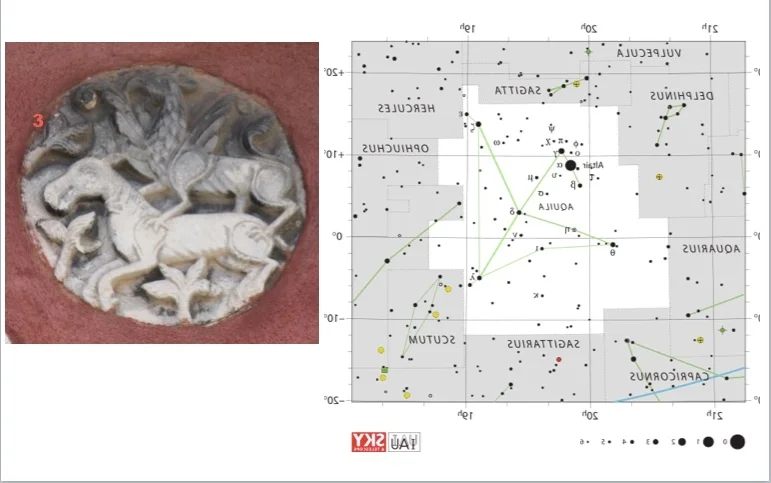

In this celestial map by the French erudite and cosmographer Ignace-Gaston Pardies (1636 –1673), we observe the constellation Andromeda as she is visible in the Northern skies: capsized on the upper part of the chart, her opened arms chained to two rocks, her head (the star Alpheratz, from the Arab Al Surrat al-faras, "the navel of the horse"), on the belly of the celestial horse Pegasus, also capsized.

Globi coelestis in tabulas planas redacti descriptio. Auctore R.P. Ignatio Gastone Pardies Soc. Jesu Mathematico, opus postumum, Paris 1674

Below her, on the left, appears the fearful sea monster Cetus sent to devour her: part dog, part horse, part fish.

Between Andromeda and Cetus in the middle of the chart, the two Zodiacal Pisces, tied together by a cord, float along the oblique ecliptic line, between Aries (up left) and Aquarius (down right). As if they were a venomous spout sent out by the monstruous Cetus, they move menacingly towards the unlucky Andromeda, one of them, the Northern one, preparing to bite her at the side, as to anticipate her horrid fate; the other Fish swims near the celestial Equator, along Pegasus' back. Andromeda's rescuer, the hero Perseus, is approaching, but he's still out of sight, beyond the right margin of the chart.

What happens if we, observers on the Earth, move southwards?

Little by little, Andromeda turns on herself, becomes a standing figure. The Northern Fish, or Piscis Boreus, penetrates her side and moves across her figure, and also the other Fish, the Southern or Piscis Australis, changes accordingly its relative location. At first, it superimposes the Boreus; then keeps moving downwards, landing among Andromeda's feet, like here:

(From top left, clockwise): Equuleus, Pegasus, Andromeda, Aries, Triangulum.

Constellation cycle derived from Alfonso X of Castile, Libros del saber de astronomia

English, circa 1400

Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, MS Ludwig XII. 7, fol. 3r

And what happens if we keep moving on the surface of the Earth?

Andromeda (now upright), meets Cetus the sea monster, and becomes one with it, creating a strange hybrid. Like (more or less) in this reconstruction:

Andrometa meets Cetus

Graphic elaboration from Gaston Pardies' chart.

We cannot say, however, that Cetus has succeeded in devouring her after all; because his head (and fearful mouth) remain on the opposite side. Let's say, that from the meeting of Andromeda and Cetus a new being appears, half woman, half sea creature: a monster or hybrid with two heads facing opposite directions, plus a big fish near the woman's side; a group very similar to that of the Venetian patere considered at the beginning.

According to this reconstruction, however, Andromeda is not actually 'carrying' the fish under her arm; the fish is still 'hitting' her on the side as before, while she just suffers passively its assault.

To understand how Andromeda actually starts to carry the fish, let's consider the following fine detail from the byzantine floor mosaic in the Church of Petra, Jordan (500-50 AD).

Portrait of a lady with the attributes of Andromeda. Floor mosaic, 5th century AD.

Petra (Jordan), Church

A lady named Verina is portrayed with some interesting attributes related to the Greek myth of Andromeda: the fish, which now she is carrying under her arm, is accompanied by the harpe in the other hand (now this rather fixes the reference, as the harpe was the characteristic weapon of Perseus). Another 'Andromedan' attribute of this figure is the beautiful round exposed breast (only one); this, probably because the celestial Andromeda has on one breast (only one), a large shining star.

As for the pinniped fin of the Venetian "syren", an interesting literary source tells us that in the Islamic tradition Andromeda was sometimes called "the Seal"; the learned author, however, is unable to explain the motive of this strange association.

The reference comes from the erudite Lutheran bishop Mattia Martinio (Freehagen 1572-1630).

A follower of the philological approach of the Benedictine humanist Hermannus Piscator, Martinius cultivated the ancient languages, and taught Hebrew, Chaldaic and Syrian in Paderborn and Brema.

In his ponderous Lexicon Philologicum, he observes:

"Quare ita [=Morus] Procyon ab illis fanaticis vocetur, non magis quaerendum,quam quare Gallina dicitur Rosa ab iisdem: aut quale Gemini sunt Pavones, Andromeda vitulus marinus, Heniochus Mulus Clitellatus".1

_______________________

1. Lexikon Philologicum, praecipue etymologicum et sacrum: in quo latinae et a latinis auctoribus usurpatae tum purae tum barbarae voces ex originibus declarantur, Francofurti ad Moenum, 1655, Heniochus, sub vocem.

_______________________

In spite of its disdainful accent, this observation is very valuable, precisely because it keeps track of some traditional Islamic denominations of the constellations that would otherwise be lost to us.

Martinio's observation here is not original, being lifted almost literally from another source about seventy years earlier, Scaliger's comment to Manilius' Astronomica. 2

_______________________

2. M. Manilii Astronomicon cum Josephi Scaligeri auctoribus curis edente Joh ..., Argentorato, Bokenhoffer, 1555, p. 440: "Andromeda phoca, aut vitulus marinus" ("Andromeda [they call] a seal, or sea-calf").

_______________________

The dismissive attitude in both Scaliger and Martinio is a reaction against the attitude of some Islamic astronomers and cartographers, who, literally faithful to the prescription forbidding the representation of human figure in art, had proceeded to redraw the entire map of the constellations without human figures, only using things and animals. Thus, Virgo the Maiden had become a Sheaf of Wheat, Heniochus (Auriga), a Mule with Panniers, and so on. This, objected Scaliger in his usual vehement style, not only seriously disrupted the classical sky, making the Greek and Roman astronomic references barely understandable; but also led to some other serious inconvenience. For exemple, the constellation Boötes, being no more human, had no more a hand with which to hold his sickle, Marra, or Falx Italica; so that the sense of his classical gesture (raising his sickle to call people to harvest), went lost.

However, it appears that the animals or inanimate things used by the Islamic astronomers as substitutes for the ancient Western figures were not choosen randomly, but in continuity with some other local linguistic habit or popular denomination.

That would explain why, reading these ancient denominations while looking at the Venetian Medieval sculptures (and not only Venetian), we feel a sense of familiarity, of reconnection.

In other words, it makes some sense to know that Two Peacocks could be the Gemini, a Rose the Pleiades ("Gallina"), and so on.

Thanks to the denominations documented by Scaliger/Martinio, for exemple, we understand why our hybrid Venetian Andromeda walks on finns; not fish, but seal-like finns (Scaliger's "phoca", seal).

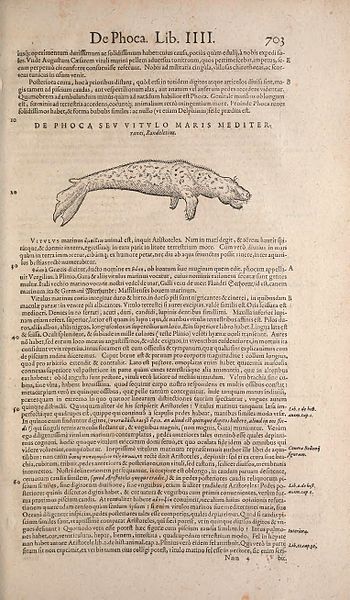

The "vitulus marinus", or "sea calf", quoted by both authors, appears of less easy interpretation, being sometimes represented like a seal, sometimes as a more or less fantastic four-legged beast, half a seal, half a dog. Here a text in which "phoca" (seal) and "vitulus marinus" (sea calf) are used as synonym, with reference to the now very rare seal of the Mediterranean:

Conradi Gesneri medici Tigurini Historiae animalium liber IV : qui est De piscium & aquatilium animantium natura : cum iconibus singulorum ad viuum expressis ferè omnibus, Francofurti ad Moenum, 1604, II, p. 703

Jan Jonston (1603-1675), Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri, cum aeneis figuris, Johannes Jonstonus, medicinae doctor, concinnavit

Amsterdam, Schipper, 1657, tav. LXVIII

Therefore, I think that we cannot be too disturbed in meeting a four-legged version of our "Phoca" among the patere of the "Woman with fish" reproduced at the beginning of this post.

Perseus, Ketos the sea monster, and other marine creatures: dolphins, an octopus, and a seal.

Apulian red-figure amphora, 4th B.C.

Malibu, The J. Paul Getty Museum

Our Venetian Andromeda, made one with Ketos the sea monster, opens interesting new perspectives for further exploration.

Her celestial genesis apperar to have things in in common with the Middle-Eastern goddess Derketo, and with some Phoenician coins, showing hybrid syrens holding fishes in their hands.

This needs, however, to be the matter for another post.

Derketo the Syrian Goddess. From: Athanasius Kircher, Oedipus Aegyptiacus, Romae : ex typographia Vitalis Mascardi, 1652-1654, 1652